The Managerial Leap: Opportunity or Obligation?

Practical Insights to Navigate Career Transitions and Leadership Roles

Welcome to Coaching Contemplations, a newsletter full of ideas and insights that will help you equip yourself with game-changing strategies in leadership and coaching to succeed at work and achieve your goals.

"You can't stumble if you're not in motion."

Richard Carlton (3 M's Architect of Innovation)

A core principle of effective leadership is making decisions. The more senior you get, the more you must get used to making decisions based on incomplete and imperfect information.

Given my line of work, it's hardly a revelation that I frequently coach clients on honing their decision-making prowess. Whether it's pushing them beyond their comfort zones to explore unconventional solutions or introducing structured frameworks to mitigate cognitive biases, the goal remains the same: better decisions.

In recent months, I have been mostly writing about what it means to manage people and how it differs from being an individual producer.

If you are reading this article because you've just received your first opportunity to manage people or have a chance to step up and take on even more managerial responsibility, let's use what we have learned in recent articles:

This will put you in a better position to decide how best to proceed.

No one has to become a manager. Becoming a manager of people is an opportunity. Not an obligation. Linda Hill, in Becoming a Manager, states

In accepting the promotion to manager, the new managers consented to more than new job responsibilities. They committed themselves to form a new professional and personal identity.

She further writes,

Managerial candidates must be as brutally honest with themselves as possible. Am I being realistic about what, as far as I can discern, the role entails? Do my career interests, aptitudes, knowledge, and skills fit the job's requirements? Is my technical background solid enough to build a managerial career on?

Some of my coaching clients didn't ask these questions before first stepping up, and they certainly did not appreciate the new identity they had unwittingly committed to. One client was rapidly rising through the ranks in a boutique consulting firm. They were one of the top handful of individual contributors at the firm. Inevitably, their management, supported by the human resources business partner, assumed they would want to manage people and could become good at it. It is common not to be asked. Since you are ambitious and talented, there is a presumption that you will want to manage, which is the default management perspective in the system around you. After I had started working with them, it soon became apparent that they didn't want to manage people. They didn't enjoy it, and because the incentive structure rewarded individual contributions rather than team-based performance, they weren't rewarded for doing it well.

My client had the technical background to build a managerial career. However, they hadn't been honest with themselves about their career interest and, consequently, their aptitude for managing others. The tension between spending time to get better with tasks or people is more common than you might think. Busy, driven people rarely take the time to pause, lift their heads, and reflect on the future - to ask and answer the questions that help determine why you might want to manage. My client ended up managing people by default and without being trained to do the job. The assumptions kept accumulating one on top of the other: the mentorship framework was working, even though their boss had changed frequently and, most recently, was based four thousand miles away. They were ambitious, so they must want to add new people management responsibilities, their success as an individual contributor signalled they would be a good manager, etc. No one took the time to understand that managing is an opportunity, not an obligation.

To Manage or Not to Manage

The phrase "to be or not to be" is one of the most famous lines in English literature. It originates from William Shakespeare's play Hamlet. This soliloquy, delivered by the character Prince Hamlet, encapsulates profound existential themes and reflects on the nature of existence, suffering, and the human condition. The phrase has transcended its original context, becoming a system of existential thought and human introspection. "To be or not to be" invites us to reflect on our personal and professional choices.

I invite you to reflect on a crucial professional choice: to manage or not to manage - to step up or to stay where you are.

In addition to ensuring you have answers to why you might want to manage people, I have a request for those of you considering taking on a new role. It doesn't matter if the new job is within your existing organisation or if it involves a move to another employer. It is as relevant for the person considering becoming a first-time manager as the tenured executive considering a step up into the C-suite. I ask everyone to perform rigorous due diligence on the new job, the new team, and, where relevant, the organisation you will be joining.

Carrying out robust due diligence is a WIN | WIN | WIN. For you, your new boss, and the new team. And yet, the bid/offer between what people expect when they sign on the dotted line and what a role really is when they walk through the door for the first time seems to be growing.

Career transitions are opportunities. However, peoples' success in their careers to date does not always prepare them to operate as successfully, whether in a new culture with a different way of doing things or where technical and individual contribution is replaced by team performance. While transitions are opportunities, they also can be vulnerable times. As the adage goes, you don't get a second chance to make a first impression. The best way to recover from a false start is to avoid one in the first place. With that in mind, here are five straightforward things to ensure you fully understand before you accept your next role:

Mandate: What are you being hired to achieve? Is this a turnaround situation, maintenance and sustaining the current performance levels, or a start-up and new venture?

Have answers to the following questions:

What type of role is this? An already high-performing team is about sustaining success. Hence, there will be fewer opportunities to make changes in the short term. Fixing a poorly performing team or a business in trouble requires radical changes to improve performance or realign the people.

What flexibility do you have to change the team if there are underperforming subordinates?

Accountability: What will you be held responsible for? Obvious, but too often, people will answer this question with generic or ambiguous responses. Specificity is incredibly helpful, especially in the first 100 days of any new managerial role.

Have answers to the following questions:

How will you know you are being successful?

What is not within your remit but others might reasonably assume is?

What are the incentives at work? Specifically, what is the mix between individual and team-based incentives and do you have any influence on them?

Priorities: What is your understanding of how the hiring manager views the urgent deliverables for you? You will form your own opinions and views, especially of the early wins that help build credibility, but this initial guidance is essential.

Have answers to the following questions:

What are the day one tasks?

What live problems or opportunities will you face upon starting the role?

Reporting Lines: Who will you report to and be accountable to? Who else, as matrix reporting is increasingly common? Your early success will depend on your relationship with your new boss and understanding their preferences and way of doing things.

Have answers to the following questions:

If you have several reporting lines, who will (really) pay you at the end of the year?

Let's not delude ourselves: as already mentioned, there are many bad managers who want to be successful rather than effective. In every environment, you will always have to deal with forceful, often belligerent people who prefer consent to collaboration. What type of manager is the prospective new boss?

How settled is your prospective boss in their role, or will they likely change soon, so you will have the risk of working for someone unknown?

What boundaries exist between your new boss and the level below you? Will your team members find it easy to bypass and arbitrage you if they don't like what they hear from you and speak with your boss?

Resources: What resources will you have access to, such as the size of the team, the number of your direct reports, and key financial resources? Too often, I see people arriving without the teams they thought they would have and so struggle from day one to deliver the early wins.

Have answers to the following questions:

Who are the people directly you will be responsible for?

What scarce resources, financial or otherwise, e.g., technology investment dollars or the size of the balance sheet, will be available to support your new team?

Your aim with these questions is to make the implicit explicit and make the most informed decision possible. Write down your answers to the questions. I recommend emailing the person you will report to should you accept the opportunity. Lay out your understanding of the essential points from the five topics: mandate, accountability, priorities, etc. Start by saying something like, "From all the conversations and meetings in the past few weeks/months, this is my understanding of the role…" and then ask, "Is there anything crucial that you feel I have misinterpreted or misunderstood?" Doing so will ensure you have a robust understanding of what you might be walking into; you will reduce the risks inherent in starting a new role and demonstrate to the new boss that you are thoughtful and understand what needs to be done.

You are unlikely to have all your questions answered. A lot of bosses, whether they admit it to themselves or not, prefer to have some ambiguity and not to make the implicit explicit. Why? Because they are incentivised to do so. The lack of clarity allows them to retrade on you and free option you because, in all likelihood, this is what they get from above. Not fair? Sorry, that is life, especially in these roles and organisations. Your goal is to have clarity around the crucial 80% of things. The task of documenting your understanding should help to reduce the chances of being retraded on. It won't eliminate the risk, but it will be mitigated. If you aren't sure, then take a pause and try to step back to review what you know so far. These new opportunities usually gain a life of their own and a momentum that makes it difficult to pause and step back. As much as it is possible to do so, reach a decision on your terms.

A sign that your prospective new boss doesn't have a good handle on the situation or understand what the role requires is a job description that spans multiple pages. The most egregious example I have seen is for a client interviewing, where the job description was five A4 pages long. It contained two pages labelled "Main activities and responsibilities" and another "Additional Key Requirements" page. The document finishes with the following: "This job description indicates the expectations of staff at this level. Job descriptions are not exhaustive, and you may be required to undertake other duties of a similar level and responsibility." I kid you not. This sort of document should come with a health warning and be a warning sign that the prospective boss does not have their stuff together. If they cannot be bothered to provide clarity concisely, then what does that say about their approach to work and the people who work for them?

"More red flags than a bullfighter's laundry basket."

Sharon O'Dea

Conducting a Personal Pre-mortem

I have previously stated that the best way to recover from a false start is to avoid one in the first place. A powerful technique for doing that is a premortem. You have probably heard of a post-mortem when coroners and physicians examine a dead body to determine the cause of death. A premortem, the brainchild of psychologist Gary Klein, applies the same principle but shifts the exam from after to before. It is an effective method for making better decisions, especially those that are more consequential and irreversible, as it helps elevate the quality of the decision. Ask yourself the following about the new opportunity.

"Assume it's twelve months from now, and your time in the new role is a complete disaster. What went wrong?"

Gary Klein describes why a premortem can be so powerful: "Unlike a typical critiquing session, in which people are asked what might go wrong, the premortem operates on the assumption the patient has died, so asks what did go wrong. The task is to generate plausible reasons for the failure." By imagining failure in advance and thinking through what caused the false start, you can anticipate and avoid potential problems once you start the new role.

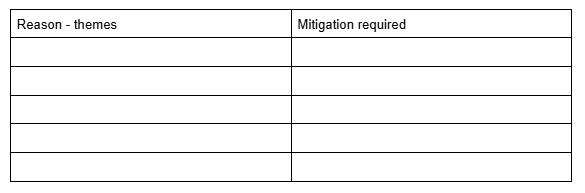

Use the following table to write down every reason you can think of for failing at the new managerial job, especially the things that wouldn't ordinarily get mentioned as potential problems working in a team. Don't hold back; define your nightmare as the absolute worst thing that could happen. Keep going and write down every reason you can think of for your failure.

By combining your insights about why you want to step up with your answers to the five due diligence questions, the reasons for failure, and how to mitigate them using the premortem exercise, you are now in a position to make an informed decision about the next step in your managerial career.

Good luck!

📫 - A quote that I am currently pondering

"The reason to play the game is to be free of it."

Naval Ravikant

🤔 - If you did have the answer to this question, what would it be?

In the matrix world of reporting that you operate, which team is your primary team and the one most important to you?